10 Best Practices in Climate Communications

Whether you’re a scientist translating why your research matters, an advocate for climate solutions, a marketer, an educator, or just a person talking to family members about climate change… you’re doing an important act of translation. These are my favorite resources for helping us do this work more smoothly.

The questions I pose are these:

How do we invite people to participate in solutions when they feel hopeless, apathetic, or dismissive?

How do we inspire a collective sense of urgency while being mindful of the despair that this awareness brings?

How can we stay motivated?

Strategic framing in climate communications considers what motivates people to change their behavior and delivers information in a way that is conscious of their biases and circumstances. Above all, it’s not about convincing. It’s about connecting. And about finding ways forward together.

Our actions today matter more for the climate than they ever have. While the task may at times feel insurmountable, there is great opportunity in the challenge. As climate strategist and self-described possibility tender Katharine Wilkinson says: what a magnificent time to be alive.

1. Uncover where missed connections happen & connect the dots.

People are worried about climate change but they’re not talking about it. Why is that?

Some say that commitment to climate action is a spectrum stretching from the fiercest delayers to the most passionate activists. These two groups are the loudest voices in the room, but they are not the majority. There is a vast middle in the United States, as data from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication reveals, who we’re not hearing from. Their silence is not because they don’t understand the science, as we’ve assumed. Actually—these folks (increasingly) believe global warming is happening and that it’s human-caused (as does the whole world). They’re quite worried about it. They’re even supportive of green policies—like investing in renewable energy, setting limits on coal plants, and regulating CO2 as a pollutant. In fact, 69% of Americans support the US becoming carbon neutral by 2050. So what’s the problem? Why aren’t we hearing this ‘middle majority’ speak up?

Two big reasons: 1) they’re not talking to each other about their concern and 2) they don’t know how they can help.

People across every background and sector struggle to connect the dots between climate solutions and what they experience day-to-day. Even fewer talk to others about the topic or read much about it in the news. These two types of missed connections are leading barriers to climate action among public audiences.

72% of US adults think global warming is mostly caused by human activities. (Yale, 2021)

46% of US adults say they have personally experienced the effects of global warming (Yale, 2021). But this number is increasing rapidly.

35% of US adults discuss global warming at least occasionally and 33% of people read about it in the news at least once per week. (Yale, 2021)

Talking about climate with others is one of the highest drivers of action. But people self-silence because:

they think others don't share their opinion (researchers call this pluralistic ignorance. There was a great write up in Grist about it.)

they're worried they'll be perceived as not competent enough to talk about it

or they fear the topic is too polarizing and politicized.

The power of explanatory metaphor, video by NNOCCI and the Frameworks Institute

When conservatives think their community doesn’t care about climate change, only 9% say they’re worried about it, according to Matthew Goldberg’s study out of Yale. But when the same people are told that a loved one cares, that number jumps to 65%.

Even so, much of the American public struggles to explain the basics of climate science, as a series of research-informed videos from the National Network for Ocean and Climate Change Interpretation (NNOCCI) illustrate, and current media coverage doesn’t help. In the video to the right, researchers ask people on the street to explain what carbon dioxide is. They find that most respondents cannot separate CO2’s role in climate change from what we breathe out. But after being exposed to an explanatory metaphor developed by NNOCCI, people are better able to explain the difference.

So. How, as climate communicators, do we motivate and prepare people to become ambassadors for climate action? Part of the task is understanding where they’re starting out—mentally and emotionally.

2. Know what mental models you’re working with.

The public draws on deeply held narratives to filter information related to climate change. Many of these cultural models are rooted in misconceptions.

We use cultural and mental models to understand the world around us. But it’s difficult to wrap our heads around a concept as large as climate change. Most of us have a hard time visualizing the problem, let alone the solutions. “It’s not that people think about climate and ocean systems the wrong way,” NNOCCI puts forth, “but rather that they do not have a way to think about them at all.”

Below are the cultural models we do have, many of which are inspired by decades-long misinformation campaigns or by cognitive biases (more on that in #4). Some delay climate action more than others.

Nature works in cycles and will fix itself. CO2 is natural and therefore good.

Mother Nature is too powerful and mysterious for humans to harm her. She will heal herself.

The ocean is vast and invincible. It’s too large to harm or else too big to fix.

Even if I do my part, other people or countries won’t. What can I really do, anyway?

How do scientists know this stuff? If you can’t explain that in a way I understand, I don’t believe you.

My observation is as good as yours, and this year winter was colder than usual.

There’s two sides to every story. Climate change is a debate.

If we do a better job of recycling and cleaning up (material) pollution, the ocean will be fine.

It’s a choice between keeping our jobs or sacrificing them to preserve the environment.

It’s too late anyway; climate change is hopeless.

This graphic from Hannah Ritchie sums up how people think about climate action. On one side we have a person’s level of optimism. And on the other, how much they think the world can be shaped/changed. She explains that only one of these quadrants drives effective climate action.

When discussing climate change with public audiences, it’s likely that you’ll cue any one of these mental models (albeit unintentionally). See this guide for a greater in depth explanation of what each of them are and this article from the NYT answering what they think the most common questions are.

Understanding which of these mental models you’re working with in any given audience is key. They point us towards gaps between expert understanding of climate science and the public’s understanding. Once we define the most prevalent gaps and understand where they come from, we can work on tackling them. These gaps tend to fall into the following categories, as this research study from the Frameworks Institute and NNOCCI finds:

The causes and drivers of climate change

How climate change works

The impacts of climate change, i.e. downstream consequences that affect humans, not just polar bears or icebergs!

How severe the effects of climate change will be (“maybe it will be okay”)

What we can do to solve it (Many consider recycling to be the #1 action they can take, while experts say it’s not the priority)

The urgency for taking action (some think of climate change as a future problem, rather than something already in motion — although this myth may not be as prevalent as we previously assumed, according to new research)

Whose responsibility it is to respond (politicians, industry, or individuals?)

How much we can trust scientists

We can overcome these misconceptions, mistrustings, and mental models only when we understand where they’re coming from. That leads us to our next point. We must go even deeper into the hearts and minds of our audience.

3. Find a way through the denial and doomism.

Denial comes in many forms, conscious and unconscious, and on a spectrum. Facts are often not enough. What then?

Cultural mindsets are mental pathways we go down many times over time. (Metaphor courtesy of NNOCCI)

The more we encounter cultural models, the more entrenched they become in our thinking. These models are like a commonly trodden pathway through a field. Built over time with repeated interactions with people and media, they’re created and reinforced. This is how we learn. And once we have these pathways, we hold onto them fiercely.

“The part of the brain that causes us to feel that familar ways are right, no matter what, is older, bigger, and stronger than the rational mind. One psychologist, Jonathan Haidt, compares the logical brain to a human rider sitting on the back of an illogical elephant. We assume the rider is in charge, making fair, just decision and directing the elephant. But it’s usually the elephant who’s calling the shots.” — Martha Beck, Way of Integrity

This evolutionary trait makes us vulnerable to the many misinformation and distraction campaigns around climate change. Add in the intensity of emotions that people tend to feel in the face of such a massive problem and we have a complicated, often unproductive cocktail. People freeze, check out, or deny. But feelings like anxiety and anger can certainly be productive too. They can motivate people to take action, as long as there’s a dose of hope thrown into the mix. It’s complicated.

So while it’s tempting to think of climate denial as a one-dimensional problem (the deniers versus the believers), climate acceptance really occurs on a spectrum. We see that with Leiserowitz et.al’s Six Americas:

“The Alarmed (26%) are convinced global warming is happening, human-caused, an urgent threat, and they strongly support climate policies. Most, however, do not know what they or others can do to solve the problem. The Concerned (27%) think human-caused global warming is happening, is a serious threat, and support climate policies. However, they tend to believe that climate impacts are still distant in time and space, thus climate change remains a lower priority issue. The Cautious (17%) haven’t yet made up their minds: Is global warming happening? Is it human-caused? Is it serious? The Disengaged (7%) know little about global warming. They rarely or never hear about it in the media. The Doubtful (11%) do not think global warming is happening or they believe it is just a natural cycle. They do not think much about the issue or consider it a serious risk. The Dismissive (11%) believe global warming is not happening, human-caused, or a threat, and most endorse conspiracy theories (e.g., ‘global warming is a hoax’).” — Yale Program on Climate Change Communications

The Alarmed segment has grown in size from 12% of the US population in 2012 to 26% in 2022. But concern alone does not inspire action. We’ll get more into that in point #5. For now, let’s narrow in on the doubtful/dismissive side of this spectrum. Science communicators often focus their energy on changing these peoples’ minds. But to do that, we need to understand how they got there.

First, we must acknowledge the deliberate misinformation campaigns funded by fossil fuel companies over decades. The How to Save a Planet podcast has a great episode on the lasting effects of these campaigns on public knowledge and what forms this misinformation takes today. Second, let’s take human psychology into account. We all have cognitive biases that can limit our desire to take action: a hyper-focus on the present rather than the future, a lack of concern for future generations beyond our great-grandchildren, the bystander effect (“someone else will take care of it!”), and the idea that veering off our current course will come with too many ‘sunk costs’. These biases factor into our collective inaction on climate change. Then, there’s the matter of identity.

Rejection of climate science and solutions usually has more to do with identity, than with data. For science communicators, it’s tempting to think that if only we just explained the science better, people would change their minds. It’s true that the more people understand climate science, the more supportive of green policies they are and the more concerned they tend to be. But ‘more information’ is not the deciding factor in climate denial, particularly when people refuse to even start the conversation. It turns out, many people in the US filter information about climate science not based on fact, but based on how well it fits in with their values and cultural schemas. This is true across the political spectrum.

Some skeptics change their minds by talking to trusted peers in non-politicized spaces, by listening to their kids, by comparing themselves to others, or by hearing about climate change more often in the news and other media (‘availability bias’ in action). But in other cases, climate denial and its equally unmotivating cousin doomism (the feeling that “it’s hopeless, so what’s the point?”) take a strong hold. With the discourses of climate delay below, we can again see that the picture is more complicated than total rejection of climate science versus total acceptance.

“The 12 discourses of climate delay” via this article from Cambridge University Press. Summarized in Climate Psyched.

So what can we do about it? See #4, #5, #6, and #7 for ideas.

4. Focus on what you have in common with your audience.

It’s not about convincing. It’s about connecting.

While we cannot shy away from the dark and devastating facts, we also have an opportunity to find the light. We can begin asking ourselves, what do we want to save? Instead of only, what have we already lost?

Before jumping into the facts and figures, you’ve got to speak to people as people—not as pupils.

The first part of your story is why someone should care about climate change. If you don’t clue them into this first, they will tune you out. Align climate change with an issue someone already cares about so it’s not competing for time and attention with other issues in their lives. — Climate Interpreter Strategic Framing

Climate change touches or will touch every aspect of our lives. You can tap into that story once you understand what matters to your audience. Get curious. “All we have to do is connect the dots between the values they already have and why they would care about a changing climate,” says atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe in her TedTalk.

It may be fishing, family, national security, or anything else. Although these interests will be unique to everyone, the values underlying them are often similar. Climate-related messaging is often most effective when it taps into peoples' desires to 1) protect people and places from harm, 2) take responsibility for solving problems that affect future generations.

As an evangelical Christian and a climate scientist, Katharine Hayhoe walks an interesting line between seemingly conflicting worlds. She is a “bridge person” creating in-roads of understanding, as Krista Tippett names in this podcast interview. It is incredibly powerful to share your own values for pursuing this work and connect them to what your audience cares about. But, Dr. Hayhoe cautions, people will immediately sniff out pandering. And emotions are not “simple levers to be pulled,” as this study warns. We have to genuinely believe in the connection we’re drawing. Each of us—given our interests, the communities we come from, the fields in which we work—has a unique power to reach people across all areas of society. And it all comes down to getting personal.

While infusing science communication with personal anecdote may seem antithetical to many science communicators, it is an incredibly powerful tool for building trust. The more people trust scientists, the more supportive they are of climate policies. But there are barriers between the public and scientists. For one, people think scientists are drawn to the pursuit of knowledge at the expense of their humanity. Our culture assumes a dichotomy between cognition and emotion, which sets scientists up to seem robot-like and cold in the eyes of the public. By getting personal, scientists are more trusted as messengers of scientific fact. Scientists who take selfies in the lab or in the field help change stereotypes and foster trust. Scientists who share their backstory with public audiences, boost their credibility. Scientists must exude both competence and warmth to be perceived as credible. Warmth, researchers found, may even be the more important of the two. It turns out, authenticity and personal connection speak louder than hard facts.

5. Appeal to hope, rather than guilt or fear.

Show people that they can be the heroes of their own story.

What solutions can look like, from Wikipedia’s climate change mitigation page.

40% of Americans feel helpless about climate change and 29% feel hopeless. The numbers are even higher among youth. The more powerless people feel in the face of climate change, the less likely they are to take action. While it’s tempting to communicate what we’ve already lost, it is equally—if not more—important to provide roadmaps towards solutions. How can we appeal to peoples’ sense of hope, curiosity, and problem-solving rather than guilt, fear, anger, or nostalgia? Hope is a great motivator for climate action (even for those who experience high levels of climate anxiety), sustained over time. And while individual action is not the largest thing we can do to reduce global emissions, collective participation is needed. Trends in psychological research about behavioral change also show that actions drive beliefs, more so than the other way around. Providing people with roadmaps about how to take actions in their local context connects all these dots.

The problem with rooting climate messaging in ‘hope’ alone is that many climate-concerned individuals struggle to express what they feel hopeful about.

Leading audiences in exercises of solutions-based thinking helps them build their muscles for engaging with the greater issues. And they’re less likely to feel preached to or shamed. Plus, cognitive bias research shows us that when people feel ownership of an idea—when they can see themselves in the story—they value it more. Keep your tone neutral, reasonable, and explanatory. And as NNOCCI suggests, “Don't spend precious communications opportunities defending the science; take the time to translate it.”

We have an opportunity as climate communicators to paint a picture of the equitable, safe future we are working toward. Visioning is a powerful tool for inspiring hope. Let’s shift away from the current discourse about loss and sacrifice, and instead show how we can all benefit from change. Cleaner air, cheaper energy, better public transportation, more green spaces—the list goes on and on.

But as Julie Sweetland notes, make sure to match solutions to the scale of the problem. Inviting people to ‘do their part’ by changing out light bulbs can lead to greater cynicism. “People intuitively sense what experts have shown: to make a difference, the changes we make need to happen on a broad scale,” she writes. Emphasizing what individuals can do in community, through policies and programs, provides a more motivating roadmap forward than narrowing in on what someone can do alone. Be careful of painting solutions with too broad strokes, too. That can leave your audience feeling confused about where they fit in. It’s a balance.

Cartoon by Tom Toro via Yale Climate Communications.

6. Make it clear how the big, amorphous concepts relate to our everyday lives.

Micro-topics are a way into understanding the big picture. So how can we “downscale” such complex problems?

A visualization from the Harvard Business Review of 18 billion coffee pods shows that they would fill a New York City block, 30-stories high. Physical space creates context for numbers that are otherwise difficult for people to conceptualize.

Emissions are amorphous and hard to conceptualize, just like big numbers. Climate communicators can struggle with breaking down the big stuff, wishing audiences could grasp the stark picture that the facts and figures alone are painting. But many people struggle to explain the basics of climate science, let alone understand how it relates to them. We need to connect the dots.

We also have those pesky cognitive biases working against us. “Humans are very bad at understanding statistical trends and long-term changes,” says political psychologist Conor Seyle, director of research at One Earth Future Foundation. “We have evolved to pay attention to immediate threats. We overestimate threats that are less likely but easier to remember, like terrorism, and underestimate more complex threats, like climate change.”

The micro is a way into understanding the macro. We can take the big concepts and break them down with tools like visualization, metaphor, and roadmaps across sectors.

Climate scientists like Dr. Hayhoe model projection data and translate it for a variety of leaders so they can make practical decisions:

“We can look at patterns of droughts in California going back 5,000 years. We can look at heavy rainfall events. Or we can look at ENSO frequency or intensity. All of this information goes into planning. It goes into planning the 100 year or the 500 year flood zone. It goes into planning what types of crops we can grow where. What our energy requirements are when we build a house. How big an air conditioner we have. It goes into all kinds of planning that we don’t think about.” — Katharine Hayhoe

Project Drawdown visualizes global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that we release into the atmosphere (on the left side) and the natural carbon sinks that absorb those GHGs back into natural carbon cycles (on the right). The visualization illustrates that there are not enough sinks for the volume of emissions we produce.

What do we want to save? How can we break the problem down into manageable parts?

To be able to end up at the place where leaders find value in her data, Dr. Hayhoe must first understand their most pressing questions.

It’s downscaling and it’s translating. Our raw output [as scientists] is daily maximum and minimum temperature and precipitation and humidity. But often what people are really interested in is how many days are going to be over 100 degrees or how many days in Minneapolis will be below freezing, or, when droughts come, how long and how strong will those droughts be?

So that’s where I started what I still do today, which is developing super high resolution information for local scales. For the city of Houston, I say, here’s what’s going to be happening to your extreme heat days, to your drought risk, to your heavy rain risk — because of course, they’re very worried about flooding; and — here’s the important part — I say, here is the difference between what your city will look like in 20 years or 30 years or 40 years. Here’s the difference between what your city will look like depending on the choices we make today. Our choices are the biggest source of uncertainty in the future.

And when people bring that down to the local scale—instead of looking at polar bears in Antarctica, we’re looking at their city. When you put it in such stark terms, then all of a sudden, everybody’s like, oh, so that’s why climate action matters. — Katharine Hayhoe

What does this data translation work look like for other audiences? Can we break down climate science in a way that the everyday person can use to make decisions in their own life?

Most of us first learn about climate change with images of polar bears, not humans, giving us the impression that it’s a far away problem. Contextualizing a changing climate around what it means for humans roots the topic in something people without scientific backgrounds grip quite immediately. Again, we can tap into the universal desire to care for our families, friends, and neighbors. Because, as we know, the fight to save the natural world is as much a fight to save people.

Climate communicators are now focusing more on 'micro-topics' (like how warming temperatures will affect asthma or food security) as a way into talking about the larger science, an approach backed up by the IPCC. It’s difficult for people to wrap their head around abstract, global metrics. We need analogies and metaphors to explain these more amorphous concepts. We need artists to illustrate the problems, the solutions, and what our future could look like. And we need storytellers to convey why it matters.

7. Find a common language. Get creative with it.

“Communication cannot simply be the dissemination of scientific facts but is rather the negotiation of meaning between the speaker and listener.”

Metaphor, personal anecdote, and data visualizations are just some of the ways to illustrate concepts so that they are understood deeply. Finding the common language that resonates with your audience will be your important task.

Images and stories that illustrate a new perspective are powerful. Take the Overview Effect—when astronauts took the first photo of Earth from the moon in 1969, we had never seen ourselves from that angle. For those that experience it, the sight of our “little blue dot” inspires a new sense of connection to our world and each other. We need designers, scientific illustrators, cartoonists, painters, screenwriters, photographers, and people across all industries to help tell the stories that will inspire hope in our future and awe in our capacity to problem-solve. Plus, research finds that integrating art and data visualizations helps audiences better understand the science and bridge political divides.

A sense of awe may play a key role in reducing climate inaction. And the latest research from Dacher Keltner on what inspires awe in people most often reveals some helpful insights here. While we might suspect the most powerful drivers of awe to be experiences in nature (ala the Overview Effect), Dr. Keltner finds that actually, for people all around the world, the most awe-inspiring thing is witnessing other people be everyday heroes.

Perhaps the most common language among us is our capacity for empathy and connection. How can we tap into that potential in climate communications? Perhaps by telling the stories not only of the solutions, but of the people making them happen. Especially those who live where we live and care about what we care about. Someone is much more likely to install solar panels if they know someone who has them or reduce their energy use when they compare themselves against neighbors. Social comparison is highly motivating. That and financial incentives are actually more effective in inspiring people to change their behavior for the better than education alone.

A huge swath of people are aware of behavioral changes they ‘need’ to make, but feel paralyzed or unable to do so given very real barriers. Education without providing alternative behaviors that are within reach may unintentionally shame people and turn them off to action.

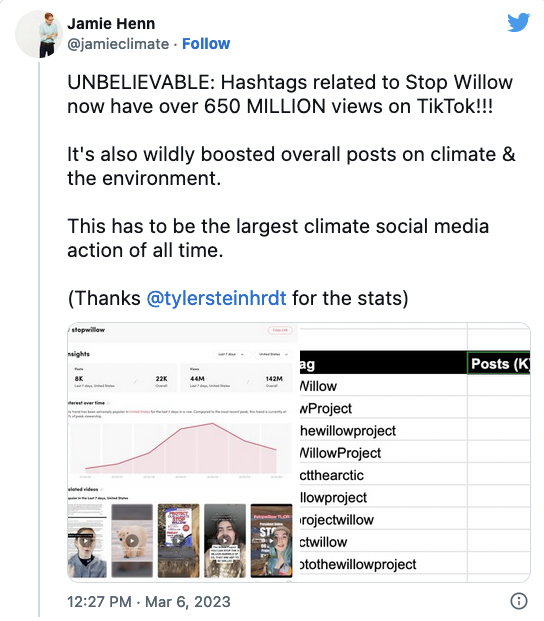

There is also something to be said for reaching people where they are—not just emotionally and geographically, but also where they spend their time. You can get quite creative with it. That’s not to say everyone has to get on TikTok. But we can elevate those for whom that is their superpower. We can collaborate outside of academic traditions and expectations to engage anyone and everyone in these conversations. It may start small. But seeds of an idea may lead to forests of changing minds.

8. Avoid communication traps.

Common pitfalls of communicating about climate science to public audiences. Graphic via Scientific American.

Just as important as finding a common language is understanding where our communication breaks down. When we’re looking at scientists’ understanding of climate change versus the public’s, word-choice is a minefield.

Susan Joy Hassol explains this beautifully in Scientific American. She illustrates common pitfalls in communicating about climate science to public audiences. A scientist may talk about “sequestering carbon”, and a layperson thinks about a jury being sequestered. When we call extreme weather events “natural disasters”, it can give the impression that they are caused by nature, rather than exacerbated by human-caused climate change. Even the words “climate change”—besides feeling politicized or polarizing to people—makes some think “climate control”, a.k.a. air-conditioning.

While a person steeped in climate news and climate work might stare in disbelief at these misinterpretations, most public audiences DO in fact carry these other associations. In climate communication work, I find we take our common language (the words we use to talk about the basics of climate science) for granted.

Other communication traps center more on narratives, rather than word choice. Frameworks research finds that the following narratives are often counterproductive to advancing climate action:

The Crisis Trap: Framing climate change as a crisis without also sharing proven solutions contributes to peoples’ compassion fatigue.

The Do One Thing Trap: Focusing on the actions individuals can take to change daily habits, rather than wider changes we can make collectively on regional and community levels, leads to cynicism—not broad change.

The Incidents and Accidents Trap: Focusing on highly publicized weather events without connecting them to larger principles of climate change is a missed opportunity. But only discussing climate change when these events occur (as opposed to connecting climate with other high-profile news) risks implying that they are isolated incidents.

The Cute Critters Trap: Climate change impacts us all (and every interconnected ecosystem), not just that cute polar bear. Humans have a huge hand in affecting these ecosystems and a duty to safeguard them. Messaging should reflect that.

9. Remember the Head/Heart/Hands approach.

How can we inspire hope and a desire to take action? And how do we channel that towards what needs to be done?

Ayana Elizabeth Johnson’s Climate Action Venn Diagram from her 2022 TedTalk, to be adapted by you!

Concern and information do not an advocate make. People must also feel a sense of agency. They must believe that solutions exist and see their place in them.

Climate communicators inspire the most action when they combine:

an understanding of climate change (the head)

hope through agency and efficacy (the heart)

and invitations to participate in community action (hands)

Calls to action that consider a person’s skillset, interests, and local context inspire them to take action rather than shut down.

People need practical road maps into climate solutions that make sense for their circumstances. Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, marine biologist and climate policy expert, developed the Climate Action Venn Diagram to help individuals reflect on these questions themselves and find where they fit into larger climate-related work.

Small movements made collectively contribute to big change.

From Everyone's a Aliebn When Ur a Aliebn Too: A Book, by Jonny Sun.

10. Be gentle with yourself. Make room for grief and for joy.

The Climate Conviction Curve by Piotr Drozd

Climate-related work takes a toll. We know this. It’s hard to look away from all the bad news without feeling guilty that we’re disengaging. Can we appreciate a hot sunny day, even when we know it’s unseasonably warm? Is it okay to still enjoy life even while the biggest challenge of our lifetimes hangs over our heads? We are increasingly worried about what the “the right way” to feel about climate change is. And we can feel disheartened when we think others in our networks and beyond don’t share our sense of urgency. What does all this mean for burnout? For our wellbeing?

Make space for climate grief, hosts of A Matter of Degrees podcast urge listeners. This is how we cope. Take breaks when you need to. Come back when you’re ready. Find meaning in your work. Connect back to why you’re doing this in the first place and share that with others. It may be cathartic. Honor the sense of loss. Hold a funeral for an iceberg even! Process your emotions in community. Share your feelings with strangers. Take moments to remember and enjoy what you want to save. Soak up the details of your life.

“If this is the work of the rest of our lifetimes, we must honour and protect space and time for staying well and whole. That means we have to surround ourselves with others who can help us carry love and trust, and hope for what might be weeks, months, or years when that’s too much for us to ask of ourselves. If this is work for the rest of our lifetimes, we also do it on behalf of people we will never know.”

— Krista Tippet, On Being